IKAT!

THE GORGEOUS PATTERNS AND BRIGHT COLORS OF IKAT WOVEN PRODUCTS ARE THE STATUS SYMBOLS OF CENTRAL ASIA IN THE 19TH CENTURY.

In pre-Soviet times in Uzbekistan, it was not just a colorful accent: ikat was the highest manifestation of the art of a fashion designer and the skill of a dyer, an indispensable part of life in those homes that could afford it, an important area of the growing urban economy, a valuable and prestigious gift, whether for a loved one or for the king.

Ikat was a link in many spheres of life: political, economic and social.

One of the reasons for the prestige of ikat textiles is the difficulty of their manufacture. The whole trick of ikat is that the colors and patterns are applied to the threads in advance, before the fabric is weaved, and only when the product is ready, the pattern appears prominently before your eyes.

Each strand of yarn can be dyed and dried up to three times. The main colors of the dyes are yellow, red and blue. Before each stage of the dyeing process, the master must tie each strand to protect the areas that should not absorb this dye. Therefore, the area that will be blue must be tied before dyeing yellow and red; The area that will be green must absorb the yellow dye, then it must be tied for the red and then unbound for the blue, so that the yellow and blue together make the green.

IKATS WITH SOME VARIATIONS WERE PRODUCED IN MANY REGIONS OF THE WORLD

The word “ikat” itself comes from a Malay term meaning “to bind.” Central Asian weavers, who worked with the ikat technique, used fine, dried silk threads for weaving. The warp, whose threads were located across the weft threads, was usually a soft, unobtrusive chintz.

The ikat technique was also used in other places, but in Central Asia things were different. Their fabrics turned out to be the most striking: colors reminiscent of precious stones, with very clear prints. You won’t see this anywhere else in the world.

The ancient cities of Central Asia, located along the northern Silk Road, were famous for centuries for the production of luxurious fabrics. As for ikats, their main production began in Bukhara and spread to Samarkand, and then to the Ferghana Valley. It flourished in the early 19th century and essentially died in the 1920s and 1930s, when Soviet power came to the region. People who are familiar with Islamic art and its language immediately grasp the connection with the tradition, but note that it has really been raised to a new level here.

Products of the early period are often distinguished by rapid color transitions from one area to another, without clear distinctions between the main pattern and the background. The shape changed in the mid-19th century, when craftsmen had mastered the technique well. “In the mid-19th century they were ready to create new drawings. And, as you can see, between 1850 and 1880 there was an explosion of new ideas.

The previous patterns were repeated, but not exactly. The artists did not stagnate. When trying something new, they followed traditional patterns but interpreted them differently. The art of ikat masters can be compared to jazz improvisation: against the background of repetition of old themes, new elements are added and new melodies emerge.

Old ikat masters said in the 1940s and 1950s that they were driven by a desire to convey a seasonal mood, for example by using abstract figures based on natural forms.

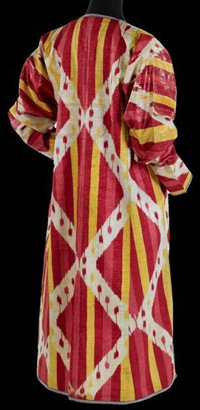

Although the designs are complex and the production process is time-consuming, the simplest garments were made from fabrics using the ikat technique: women’s dresses and shalwars, T-shaped tunics, for both men and women. Patterns of women’s robes differ only in small folds under the sleeves, so that the top of the robe fits a little more to the figure and a slightly looser cut at the bottom.

The lining of the tunic was also made bright, but not from ikat, but from printed cotton fabric. Ikat was too “expensive and prestigious” for most people. It was a luxurious fabric for special occasions. Everyone wanted to have it, but not everyone could afford it: for this it was necessary to have a high income. Depending on a person’s income, their wardrobe could have just one such product, or dozens.

Not a single piece of old ikat was thrown away. A worn robe for an adult could be altered for a child or used as a trim for other clothing.

Although fabrics and garments with the ikat technique were made in the urban centers of Central Asia – oases along the Silk Road – they were also used by nomads in the interior of the country, as well as by upper-class urban residents. half.

However, in the 20th century, the prestige of Central Asian ikats led to the decline of the industry that produced them. Because, for example, private workshops – fashion designers, dyers, weavers and tailors, sometimes from different ethnic and religious groups – could not fit into the ideal of collectivism preached in the Soviet Union. They tried in every way to somehow preserve the tradition, but, unfortunately, when the Soviet regime came, ikat was considered a typical product of the middle class, for wealthy clients, and therefore, in essence, they banned the production and the use. of this material.