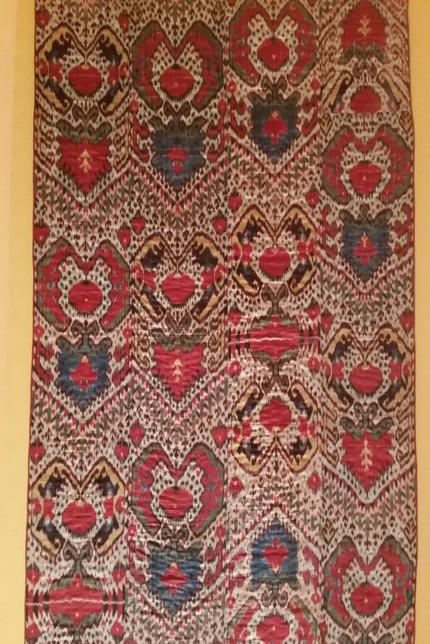

Uzbek handmade silk fabrics

Uzbek handmade silk fabrics are famous throughout the world. Sometimes they are called ikat, sometimes – abr fabrics.

Where did these names come from and what do they really mean? What are their differences? What is the symbolism of the patterns? What do history and religion have to do with fabric composition?

Especially for readers of Fergana, who are not too familiar with various aspects of textile production, but are keenly interested in the cultural heritage of Uzbekistan, Doctor of Art History, Professor, Leading Researcher at the Institute of Art History of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan Elmira Gul answers these and other questions.

The phenomenon of ikat/abr fabrics, in particular, is that in the history of world civilization they were not just textiles. If we turn to the past, we will see that in different historical periods these fabrics had an amazing fate.

SPECIAL METHOD

Elmira Gul, photo by Andrey Kudryashov/Fergana

In general, these are fabrics dyed using the reserve method. The essence of the method is to gradually “reserve” the warp or weft threads (that is, wrapping certain areas in order to protect them from dyeing) followed by dyeing the unwrapped areas, even before the threads are threaded into the weaving mill.

This method has been known since ancient times in Egypt and China, India and Indonesia, Mexico, Peru and Japan, in Central Asia.

ℹ️ The term ikat, applied in scientific and popular literature to the entire body of reserve-dyed fabrics – cotton and silk – is quite late, and is not their self-name. It was proposed by the Dutch researcher Gerret Pieter Rouffaer, who studied Indonesian reserve-dyed fabrics at the beginning of the twentieth century, and took as a basis the Malay-Indonesian definition “mengikat”, which means “to weave, knit, join, wrap, entwine everything around.”

Also, the term ikat began to be used to refer to ready-made decorative fabrics dyed using the reserve method, regardless of the place of their production. Uzbek abr fabrics (from abr – cloud, although there are other interpretations) – atlases, khan-atlases, etc. – are part of the general body of ikat, but they differ in that during their production only the warp threads are dyed. However, the monotonous method of dyeing did not prevent them from becoming a leader in terms of the wealth of color combinations and ornamental solutions that delight the whole world.

They were the bearer of certain messages, a means of regulating social, economic and political relations.

BEFORE IKAT

I would like to remind you that before the medieval world became interested in ikat, there was another fabric, no less famous – silk samit, a strategic product of the early Middle Ages, a symbol of luxury and success, equally loved in the West and in the East. Samites – twill fabrics with a printed pattern – were produced in China, Central Asia, Byzantium, Iran… The trade in samites gave the name to the famous trade route – the Great Silk Road. The exceptional value of these fabrics made them the most valuable international currency, not only a cultural, but a political symbol of the era.

Sogdian product made from samit fabric. Photo pinterest.ru

Ikat, Yemen, late 9th – early 10th centuries. Cotton, reserve dyeing, ink. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by the author

A brief reference to silk samita is needed in order to remind: with the emergence of Islam, the production of silk samita in the territories that fell within the circle of spread of the new ideology soon died out, they were replaced by ikat – a reserve-dyed fabric.

To what can we associate such a radical change of priorities? Only one factor comes to mind – religious.

This method has been known since ancient times in Egypt and China, India and Indonesia, Mexico, Peru and Japan, in Central Asia.

ISLAM CHANGED EVERYTHING

Ikats produced in the Arab world – they were known as asb – became carriers of new ideas, a means of spreading a new aesthetics and a new faith – Islam. Here we must pay attention to three factors.

The Arabs offered the world exclusively cotton ikat (although the earliest known examples, presumably from East Turkestan, 6th-7th centuries, discovered in Nara and now kept in the National Museum in Tokyo, were silk).

Ikat, Yemen, late 9th – early 10th centuries. Cotton, reserve dyeing, ink. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by the author

The choice of material is due to the fact that the Arabs were followers of egalitarianism. Accustomed to simplicity and functionality in all spheres of life, they advocated social equality, condemned luxury, the production and wearing of silk clothing, and the use of utensils made of precious metals. It is known that the Prophet himself forbade men to wear gold rings and bracelets, as well as expensive silk. According to the Koran, silk was allowed only as a reward in the high world. That is why Arabic ikat were made exclusively from cotton.

The second factor is the decor of Arabic ikat. These are exclusively abstract patterns. For the Muslim world, abstract decoration was a conscious choice, a reflection of the aesthetic priorities of Islam, inspired by the indescribable God.

Finally, the third factor is inscriptions. The Arabs were the first to produce ikat with inscriptions on them – tiras. Calligraphic lines were embroidered or applied to fabric with ink. As is known, calligraphy had a sacred meaning in the culture of Islam. As a result, the epigraphic decoration emphasized the highest status of fabrics of this type. It is no coincidence that they were made in specialized workshops under royal supervision.

BUT STILL SILK

At the same time, you can argue that the famous ikats of Central Asia from the 19th – early 20th centuries are silk. Indeed, with the collapse of the Caliphate and the rise of local dynasties to power, silk reappeared in the textile production of Islamic countries – the demand for luxury goods turned out to be stronger than religious beliefs. But restrictions on wearing purely silk fabrics persisted for centuries. As the Russian Orientalist and diplomat Peter Demizon, who visited Bukhara in 1834, mentioned, pure silk “could only be worn by women, since it is believed that if a Muslim wears clothes made of pure silk during prayer, his prayer will not reach Allah.” .

In the 19th century, know-how appeared – semi-silk ikat. The warp of this fabric is cotton, the weft is silk. Such fabrics were probably a kind of compromise with conscience, when a person wore silk, despite religious prohibitions, but at the same time was pure before God, since the fabric was not purely silk.

It is also interesting that abr fabrics were not intended only for the elite, like silk samita, for example, which was worn only by the nobility. The first ones were quite democratic. Thanks to archival photographs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we can see that ikat was worn by everyone – representatives of different ethnic groups and classes, poor and rich, city dwellers, villagers and steppe dwellers…

Strange as it may sound, they were made elitist already in the 20th century by Europeans and Americans who became interested in collecting these fabrics. They also wore these things, making them a sign of belonging to a certain Orientalist subculture, sometimes closed, not for everyone.

At the same time, you can argue that the famous ikats of Central Asia from the 19th – early 20th centuries are silk. Indeed, with the collapse of the Caliphate and the rise of local dynasties to power, silk reappeared in the textile production of Islamic countries – the demand for luxury goods turned out to be stronger than religious beliefs. But restrictions on wearing purely silk fabrics persisted for centuries. As the Russian Orientalist and diplomat Peter Demizon, who visited Bukhara in 1834, mentioned, pure silk “could only be worn by women, since it is believed that if a Muslim wears clothes made of pure silk during prayer, his prayer will not reach Allah.” .

In the 19th century, know-how appeared – semi-silk ikat. The warp of this fabric is cotton, the weft is silk. Such fabrics were probably a kind of compromise with conscience, when a person wore silk, despite religious prohibitions, but at the same time was pure before God, since the fabric was not purely silk.

It is also interesting that abr fabrics were not intended only for the elite, like silk samita, for example, which was worn only by the nobility. The first ones were quite democratic. Thanks to archival photographs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we can see that ikat was worn by everyone – representatives of different ethnic groups and classes, poor and rich, city dwellers, villagers and steppe dwellers…

It is difficult to talk about the distinctive features of the production of abr fabrics among various ethnic groups living within the borders of the Uzbek khanates. This difference is extremely arbitrary and is more likely not ethnic, but purely geographical. This is due to the fact that in places where peoples live together, a kind of symbiosis of cultures has developed. In such situations, it is not ethnic differences that come to the fore, but economic and cultural ones. The differences were mainly in color preferences, scales and proportions of patterns…

IKAT IS A BAROMETER

Throughout the twentieth century in Uzbekistan, abr fabrics continued to remain a kind of barometer of the mood of society, an indicator of political conflicts.

In the first decades after the establishment of Soviet power, handicrafts, including the production of silk fabrics, were outlawed, as private property and means of production were prohibited. However, it was impossible to eradicate the love for colorful silks. As a result, the Tashkent Textile Mill was opened in 1934, where people’s favorite fabrics began to be produced using mechanical printing.

In the 1930s, abr silks began to be associated with the Uzbek national identity, as evidenced by numerous films and photo chronicles of those years. Young girls with open faces and dresses made of khan-atlas became a symbol of the renewal of society.

A new surge of interest in these fabrics occurred in the 1970s – mid-80s, during the period of so-called “stagnation”, when there was a revival of national traditions “from below”, and not “from above”. During these years, interest in traditional values and the roots of national culture was again noticeable in society.

The ancient art of hand-weaving silk was fully revived after 1991, when Uzbekistan gained independence. Changes in economic policy and the emergence of private entrepreneurship allowed artisans to once again establish handicraft production of silk fabrics.

At the same time, practice shows how vulnerable this production is. As soon as the pandemic broke out, the largest silk weaving enterprise in the Fergana Valley – Margilan’s “Edgorlik” – fell into a crisis situation and was almost on the verge of closure.

Such excesses show how fragile the world of traditional culture is in modern industrial society and how much it needs protection and careful preservation by the state.